Category: defense

Innovation Through Procurement: Across Europe

Spurred by the report on The Future of European Competitiveness led by former Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi, institutions across Europe are examining how to promote innovation through public procurement. On November 13-14, 2024, GW Law’s Christopher Yukins met with his colleagues in Europe about these ongoing initiatives.

At the University of Utrecht’s School of Law, Professor Yukins met with Professor Elisabetta Manunza and her team to discuss academic cooperation between the EU and U.S. procurement research communities. Among other things, they discussed ongoing research with NATO’s Defense Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic (DIANA). University of Utrecht Associate Professor Willem Janssen and University of Auckland professor Marta Andhov have dealt often with issues of innovation through procurement in their award-winning podcast, BESTEK. Utrecht Assistant Professor Nathan Meershoek has written extensively on the challenges of innovation in defense procurement; NATO’s unit to foster innovative technology, DIANA, is one answer to those challenges.

DIANA was established by NATO to find and accelerate dual-use innovation capacity across the Alliance. DIANA provides companies with the resources, networks and guidance to develop deep technologies to solve critical defense and security challenges.

Professor Yukins also met with Stephan Corvers and his team in s-Hertogenbosch. The CORVERS consultants are legal experts in strategic public procurement, innovation and contracting. CORVERS has been asked to help assess best practices in procurement for innovation, from around the world, on behalf of the European Assistance For Innovation Procurement – EAFIP, an initiative financed by the European Commission (DG CONNECT) to provide local assistance to public procurers to promote innovation and best practices.

A few days after those meetings, the European Commission announced a series of initiatives to advance innovation in procurement. Those initiatives included a public consultation on possible updates to the EU procurement directives — including, importantly, a review of how the directives might be updated to foster innovation.

EU Defense Procurement and the European Court of Justice

Professor Andrea Sundstrand – Stockholm University

Please feel free to join this interesting presentation on EU defense procurement and the decisions of the European Court of Justice. Professor Sundstrand of Stockholm University will discuss her article on the intersection of Member State autonomy over defense matters and the European Union’s authority to direct procurement rules.

Wednesday, 14 February 2024 – 3 pm – GW Law School, 2000 H Street NW, Washington DC – Stockton 306

For further information: cyukins@law.gwu.edu

US-European Defence Cooperation: Imperatives in a Time of War – by Christopher R. Yukins & Daniel E. Schoeni

This was a contribution to a special edition of the University of Nottingham’s Public Procurement Law Review on defense procurement in light of the war in Ukraine. What follows is the abstract, including the British spelling:

Rather than summarising the US national procurement regime for defence—the approach taken by many valuable contributions to this special edition, regarding other nations—this article defers to the existing literature and instead places the US practice of defence procurement law in a broader context, especially in light of Russia’s war against Ukraine. The US experience is that civilian and military purchasing are largely interchangeable, and that hard lessons learned from both quarters, such as in the procurement of supplies in a battle zone and the elimination of trade barriers, could be used to advance the cause of Ukraine and its democratic allies in the current war. The moral imperatives presented by the war in Ukraine are obvious, and this brief piece concludes that legal practitioners in our discipline, even if they are not specifically defence experts, can share a common skillset crucial to preserving democracy and rebuilding Ukraine, despite this terrible war.

This article was first published by Thomson Reuters, trading as Sweet & Maxwell, 5 Canada Square, Canary Wharf, London, E14 5AQ, in the Public Procurement Law Review, 32 Pub. Proc. L. Rev. 445 (2023), and is reproduced by agreement with the publishers. For further details, please see the publishers’ website. The manuscript version of the article is available here on the Social Science Research Network (SSRN).

GW Law Webinar – A Tumultuous Year for Trade

Thursday, 3 September 2020

This year has seen an unprecedented rise in trade barriers – both direct and indirect – involving public procurement. Join a free 60-minute webinar sponsored by George Washington University Law School’s Government Procurement Law Program, to hear leading experts on emerging trade barriers affecting grants and procurement.

Cybersecurity Controls and the Section 889 “Huawei” Ban: Scott Sheffler (Feldesman Tucker) and Tom McSorley (Arnold & Porter) will discuss two important measures that the U.S. government is taking to address security risks – the U.S. Department of Defense’s Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC), and the governmentwide interim procurement rule and final grants guidance banning Huawei and other Chinese companies under Section 889 of the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2019.

These measures, driven in part by the broadening role of foreign firms in the U.S. government’s supply chain, and in part by the specific challenges posed by Huawei and other Chinese high-technology firms to U.S. security, impose substantial compliance burdens on contractors and grantees in U.S. procurement. For many in the U.S. government, it would be “nothing less than madness to allow Huawei to worm its way into one’s next-generation telecommunications networks,” and Section 889 and parallel initiatives (such as the “Clean Network” initiative) are intended to shield the United States.

In practical terms, the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) and Section 889 may make it very difficult – if not impossible – for foreign vendors to compete in U.S. markets

In practical terms, the CMMC and Section 889 may make it very difficult – if not impossible – for foreign vendors to compete in U.S. markets, raising questions under the United States’ international free trade agreements and reciprocal defense procurement agreements. (The vulnerabilities in the U.S. government’s information technology supply chain are the subject of an upcoming GAO report, and a separate private-sector study is assessing barriers to procurement trade generally.) Although the Trump administration, bowing to industry pressure and the Defense Department’s concerns, extended the Section 889 implementation deadline to September 30, 2020 for Defense Department contractors, the compliance burdens remain quite serious.

Trump Administration’s “Buy American” Order for Medicines – and the Biden Plan: From its start, the Trump administration has adopted a broad range of “Buy American” measures, including a recent change to federal grants rules which says that grantees should, when possible, buy U.S. goods. Although even some supporters have criticized the Trump administration’s “Buy American” efforts as ineffective, Trump’s protectionist rhetoric has undoubtedly affected the international debate over free trade in procurement.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, on August 6, 2020 President Trump issued an executive order for “on-shoring” the manufacture of essential medicines bought by the U.S. government. The order calls for limiting U.S. market-opening commitments under the World Trade Organization (WTO) Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) and free trade agreements – a process which could trigger months of renegotiations with trading partners and result in limiting U.S. access to foreign markets. Jean Heilman Grier, former procurement negotiator at the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, has written on the Executive Order.

Jean Grier has also written on Democratic candidate Joe Biden’s own Buy American plan, which also calls for broader U.S. domestic preferences. Jean Grier will join Robert Anderson, former lead at the WTO on GPA issues, to discuss trade, procurement and the upcoming U.S. elections. Jean’s recent posts: (1) Trump’s Buy American Order for Medicines, (2) Buy American legislation, and (3) Biden Buy American Plan.

Impact of the Pandemic: Of course controversial trade measures have been driven in part by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Robert Anderson co-wrote an article with Anna Mueller of the WTO on the constraints and flexibility afforded by the WTO’s Government Procurement Agreement. For their part, co-moderators Laurence Folliot Lalliot and Christopher Yukins co-wrote a piece in Concurrences, the competition periodical, on the pandemic’s lessons for international markets, including especially the pandemic’s disruptive effect on protectionism. While the pandemic exacerbated economic nationalism and trade barriers, the pandemic also pointed up the sometimes mortal dangers of cutting off international supply chains.

European Trade Measures: Roland Stein (of the BLOMSTEIN firm, Berlin) and Professor Michal Kania (University of Silesia/Poland) will discuss important developments in access to European procurement markets:

White Paper — Possible Exclusion of Subsidized Foreign Firms: Following on 2019 guidance from the European Commission to member states on abnormally low bids from vendors from outside the European Union, in June 2020 the Commission issued a white paper on “levelling the playing field as regards foreign subsidies.” The white paper launches an EU-wide consultation on how to address foreign subsidies which distort EU procurement markets; among other measures under consideration, member states might exclude vendors that receive foreign subsidies. The white paper notes that the EU continues to assess the proposed International Procurement Instrument, a measure which has received cautious support from European industry and which would allow member states to raise new barriers against vendors from nations (including potentially the United States and China) that do not cooperate in EU efforts to open procurement markets.

Exclusion for Non-Domestic Content: Article 85 of EU Directive 2014/25/EU, which governs utilities’ procurement, says that a bid may be rejected if more than 50% of the products being offered would come from nations that have not entered into a free trade agreement with the EU (such as China) – a rarely enforced restriction which, as codified in German law, was recently applied by an important German court, the Brandenburg higher regional court.

Program Moderators: Professor Christopher Yukins (GW Law School) and Professor Laurence Folliot Lalliot (Université Paris Nanterre).

European and Australian Defense Procurement — Legal Perspectives

Wednesday, February 19, 2020, 9 am – GWU Law Learning Center – Room LLC006 – 2028 G Street NW

Join Andrea Sundstrand (Stockholm University) and Colette Langos (University of Adelaide) to discuss developments in Europe and Australia in defense procurement. Professor Sundstrand will discuss how defense procurement is treated under European law, including under the leading decisions of the Court of Justice for the European Union. Colette Langos will present a “snapshot” of the law and policy landscape surrounding Australian defense procurement. The session is free, and light refreshments will be served.

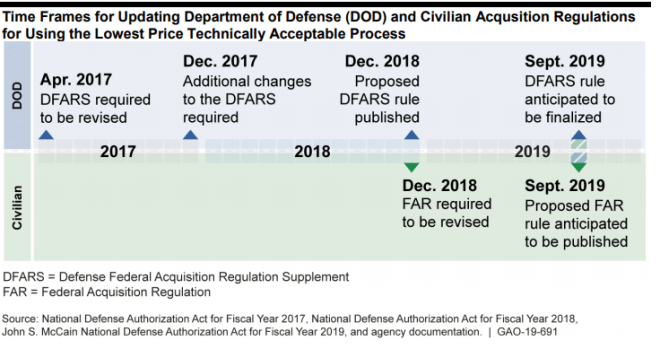

After Long Delay, U.S. Defense Department Issues Final Rule Limiting Use of Lowest Price Technically Acceptable (LPTA) Awards

The U.S. Defense Department will on September 26, 2019 publish a long-awaited final rule to implement Congress’ curbs on low-price awards. Unlike European governments, since World War II the U.S. government has come to rely heavily on multilateral competitive negotiations which trade off price and quality to ensure best value. Recent years, however, saw a resurgence of “lowest price technically acceptable” (LPTA) procurement – an award to the vendor that offers the cheapest good or service that is technically acceptable. The final rule, which reflects Congress’ concerns that the low-price method is used too often and inappropriately, may slow the use of LPTA awards.

Many have argued that the LPTA procurement method is a throwback to a more primitive form of procurement based on low price. Contracting officials, however, have embraced this return to low-price procurement. Critics have suggested that this is because low-price awards are easier to implement and explain, they reduce the nominal prices paid by the government, and awards based on low price allow contracting officials to avoid the often sticky questions raised by technical and past performance evaluations. Because price is simple and technical issues are often quite difficult for contracting officials to master, critics of the LPTA method have argued that focusing on low price reduces administrative costs and risks for contracting officials, even if the award does not result in the best value for users – a classic “agency” problem in procurement.

After long debate and numerous studies noting industry’s opposition to low-priced awards, Congress passed a series of laws intended to curb the use of the LPTA method in federal procurement. Despite early Pentagon guidance urging caution in the use of the LPTA method, Defense Department regulators took long (several years, though Congress had called for swift action) to prepare and publish a final rule implementing those statutory restrictions. Operational guidance for Defense Department contracting officials is being published as well, and civilian agency requirements will be addressed separately under a government-wide rule currently under review.

The final rule reflects a restrictive implementation of Congress’ curbs on low-price awards; in fact, the new rule is in many ways merely a “copy-and-paste” of the statutory requirements. Regulators repeatedly rejected suggestions to clarify, for example, that low-price awards should be limited to non-complex acquisitions. Regulators argued that where Congress did not impose a specific bar on low-price awards, further limitations should not appear in the rule – a markedly narrow approach, given the broad discretion allowed U.S. regulators when implementing legislation.

Despite regulators’ cautious approach, the final rule does impose important limitations on the use of the LPTA method:

- Contracting officials will have to document (but not necessarily publish) why they chose to use the LPTA method.

- Certain goods (such as personal protective equipment to be used in combat) are not to be purchased using the LPTA method.

- The LPTA method is to be avoided in contracts

and orders unless:

- Requirements can be described “clearly and comprehensively”

- Little value will be gained from a proposal that exceeds minimum technical requirements

- The technical requirements require little subjective assessment

- Review of the technical proposals is probably not valuable

- A different procurement method is unlikely to spur innovation

- The goods to be purchased are expendable or non-technical

- The contract file explains why the lowest price will reflect full life-cycle costs

Regulators’ comments to the final rule acknowledged that the government does not hold data on how often the LPTA method is actually used in practice. If, in response to this final rule, industry continues to press Congress for further limitations on low-price awards, future reforms may focus on the need for data on LPTA awards, and on greater transparency in contracting officials’ decisions to make awards based on low price.

Editor’s note: This post was updated on September 26, 2019 to include the two charts from GAO Report GAO-19-691, which was published after the final DFARS rule was released.

Professor Michal Kania – European Defense Procurement – Presentation at GWU Law School

Defense_Security_UE_Michal_Kania_Final_version – Published

Visiting Fulbright scholar Professor Michael Kania (Silesian University) will present on European Defense Procurement at George Washington University Law School, Law Learning Center 006, 2028 G Street NW, Washington, DC, from 6-8 pm on Tuesday, November 6, 2018. His presentation is linked above. If you would like to attend this open seminar, please reserve a space with Cassandra Crawford, ccrawford@law.gwu.edu.

European Commission Proposes Expanding the European Defence Fund—A Major Potential Barrier to Transatlantic Defense Procurement

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3204844

The European Commission has proposed expanding the European Defence Fund, an initiative to fund defense technology developed in Europe. As a general matter, only European firms would have access to the fund for development, and participating European nations would need to commit themselves to purchasing the defense materiel developed under the fund. In effect, this could lock U.S. firms out of billions of euros worth of European defense procurement over the coming years—despite long-standing reciprocal agreements under which the U.S. and its European allies agreed to open their defense markets. The fund was announced quietly last year and now, in the shadow of a trade war launched by the Trump administration, has evolved into a substantial potential barrier in the transatlantic defense market, and potentially another brick in a rising wall of protectionism between the U.S. and Europe.

60 Gov. Contractor para. 196 (June 27, 2018)

The Trade War Comes To Defense Procurement

In response to the Trump administration’s demands that Europe spend more on its own defense, and as part of a broader hardening of trade positions between the United States and Europe as a result of the Trump administration’s trade policies, Europe is moving forward with the European Defence Fund, which will block non-European firms (including U.S. firms) from billions of dollars in European defense spending. (Ironically, the Trump administration’s own “Buy American” initiative in procurement apparently has been stalled over the past year, and the Trump administration has pushed recently to expand foreign military sales by U.S. defense firms.) The European initiative, which goes beyond the protections of the 2009 European defense directive, may be a violation of the many reciprocal defense procurement agreements between the United States and its European allies. European officials have defended these bars against non-European contractors as “reciprocity” for U.S. security constraints on foreign ownership and control in the U.S. defense industrial base, but the protectionism of the European initiative appears to go well beyond normal security concerns — inspired, perhaps, by the Trump administration’s expansive use of “national security” as a rationale for protectionism.

In response to the Trump administration’s demands that Europe spend more on its own defense, and as part of a broader hardening of trade positions between the United States and Europe as a result of the Trump administration’s trade policies, Europe is moving forward with the European Defence Fund, which will block non-European firms (including U.S. firms) from billions of dollars in European defense spending. (Ironically, the Trump administration’s own “Buy American” initiative in procurement apparently has been stalled over the past year, and the Trump administration has pushed recently to expand foreign military sales by U.S. defense firms.) The European initiative, which goes beyond the protections of the 2009 European defense directive, may be a violation of the many reciprocal defense procurement agreements between the United States and its European allies. European officials have defended these bars against non-European contractors as “reciprocity” for U.S. security constraints on foreign ownership and control in the U.S. defense industrial base, but the protectionism of the European initiative appears to go well beyond normal security concerns — inspired, perhaps, by the Trump administration’s expansive use of “national security” as a rationale for protectionism.